BEACONS (March 2025)

Narrative mixed media, long form text and photos with datalinks interrogating faith of/within institutional relevance (Supported by The Campfuego Fund for Unemployed Writers)

We visited Portland recently for the stunning Translinear Light: The Music of Alice Coltrane. I’d never heard a harp played live before! Brandee Younger made me believe in god.

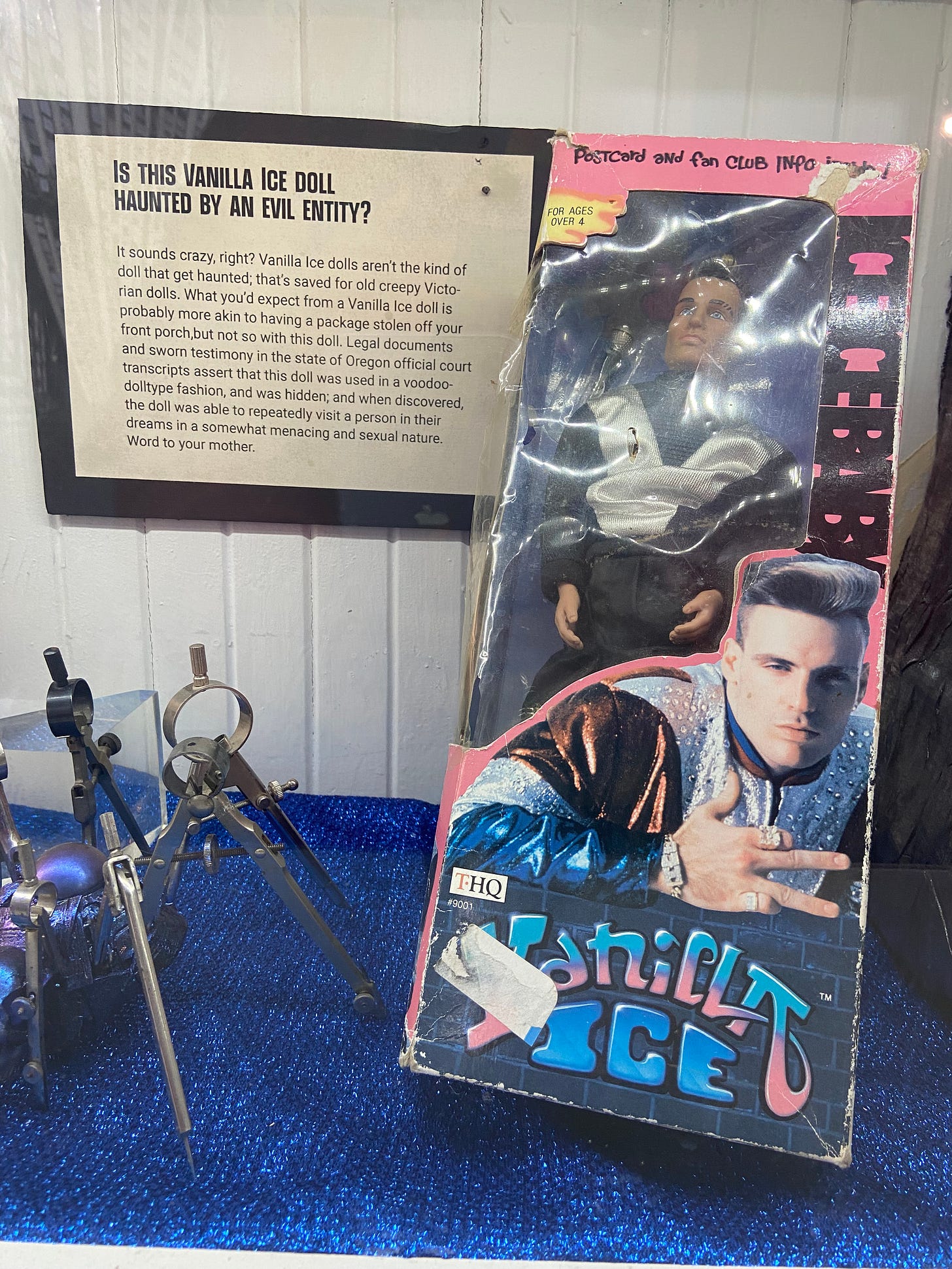

Before the show, I dragged Greg to the Freakybuttrue Peculiarium. We walked through the converted storefront packed with photocopied posters and random thrift store finds that were each accompanied by wonderfully elaborate fictions. Little gruesome dioramas of mass murders and the decorative scarab jewelry adorning an Egyptian tomb were highlights, and the story claiming a haunted Vanilla Ice Doll was a wildly creative way to commemorate the kind of trash you find when cleaning the garage.

The set-up of novelty museums remind me of middle school science fairs, with added sound effects and an occasional jump scare. There’s a “touch me” “point here” “laugh out loud and roll your eyes” warmth that is an energetic opposite of most contemporary art museums I’ve visited.

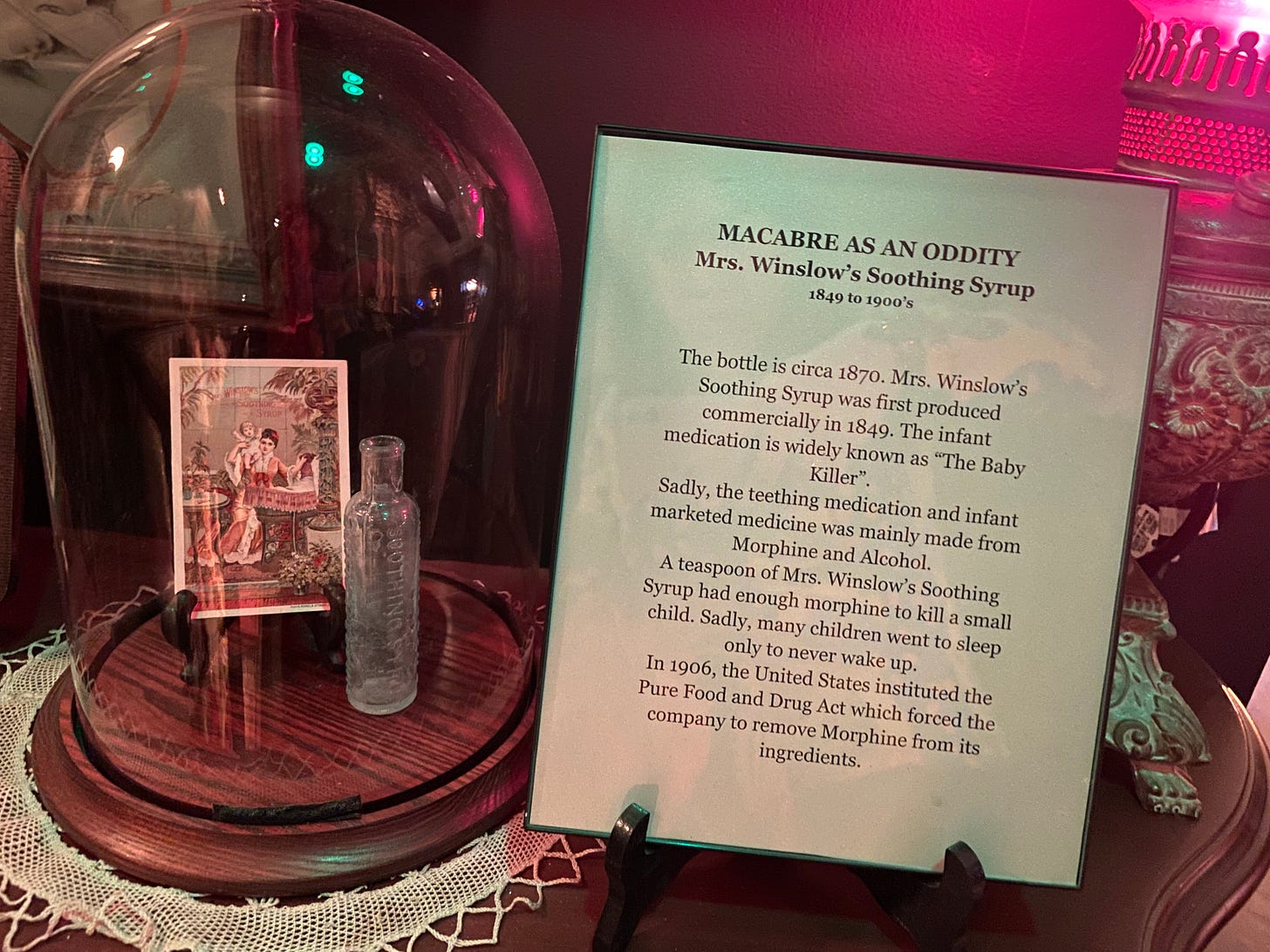

It was our lucky day because on the way back to the hotel, we found another unusual museum. I loved the Odditorium! This goth collection was devoted to vampires, medical oddities, and lacy Victorian nightmares. They had a whole section on Ouija boards, and I loved that they paired Dr. Frankenstein’s lab with a case of old school dildos.

I’m also drawn to the vintage MAD Magazine tone of these types of museums’ interpretive labels, or no labels at all, or construction paper placards that enthusiastically describe the objects on display. The interpretive materials aren’t strangled with art speak , the kind of expensive sounding language arranged in awkward syntax that insists on its artistic significance and also serves as a kind of linguistic membership to the art world. A couple of smarties studied and mapped out this highly specific language: International Art English.

I try to find novelty museums anytime we visit a new place. In Berlin, it was the Magicum. It’s subterranean and promises a comprehensive experience through the world of magic—both rabbit-out-of-the-hat type of magic and questionable explorations of religion, shamanistic practices, and witchcraft. Yes, we were the oldest people there who weren’t accompanying children, and yes, it was essentially a dank basement witch torture museum. But we got to play with pendulums and see a live magic show!

Walking around Berlin, we were inspired by all the public art. It felt organic and celebrated. The city’s dramatic history was not only referenced in the artwork inside the museums, but also visible in the converted war buildings, the remnants of the Berlin Wall, and the Holocaust memorials. A public project that left an impression on me was the “stumbling stones” which are small brass plates in the front of buildings that honor the victims of the Nazi regime at the site of their last chosen residence. The plaque states their name, the birth date, and their fate: deported, disappeared, suicide, murdered. There are currently over 100,000 Stolpersteine. This artistic remembrance project was initiated by Gunter Demnig in the early 90’s.

Berlin’s history was present and visible, an ongoing acknowledgement of the human capacity for brutality and oppression. These works didn’t feel performative or punitive—the artwork and commemorations were an effective way of reminding us that the nightmares we assign to the past are still with us, we are literally walking into them.

At the whittled core of my love for arts institutions is the belief that our collective memories and the potential futures of our humanity are interpreted, envisioned, and documented by artists and archivists. And that the ideal role of powerful cultural institutions and museums is to preserve these memories and steward the stories of the future. Especially the points in time when we failed to protect each other. It wasn’t just the visibility of history in Berlin that I found so thought provoking, it was how that visibility reflected a people’s willingness to confront and discuss darkness.

I am haunted by the images of the wire bed frames and interactive wall of desaparecidos in Santiago’s Museum of Memory and Human Rights. The surprise at seeing the carefully hand-stitched eyeholes on the klan hood at Greenwood Rising in Tulsa, OK and later wondering about the process of its acquisition. I remember everything I saw at the stunning Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL but get stuck in the memory of the mesmerizing ocean in the antechamber between the lobby and a watery mass grave by Ghanian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo. There is nothing else like it in the US. Why is there nothing else like it in the US.1

For all our romanticizing of Berlin, German cultural institutions have been silencing Palestinian artists and culture workers who stand against the US-financed genocide of the Palestinian people. Strike Germany mobilized in response. Their demands include the end of punishing people who express critical opinions of the State of Israel, to stop equating protests against genocide to anti-Semitism, and, in their own words “… As Gaza is being annihilated, artists and cultural workers have a responsibility to fight for internationalist solidarity and the right to speak out against the ongoing massacre.”

Responsibility and remembering. Serious question: who are these institutions really for? The answer shifts depending on the geography and scope of the institution itself. I’ve worked in Southern California arts orgs & nonprofits for over 20 years, mostly in Orange County, so plenty of over-the-top parties and bewildering exhibition language. Fine, whatever, self-indulgent but not the worst thing. It’s the reluctance to engage in a broader intellectual discussion about actual culture that gets me. Example: a well-resourced museum used AI in a recent exhibition without a disclaimer. Some patrons noticed and got upset. Instead of owning up to the error or taking the opportunity to host a provocative community discussion about the role of AI in arts and museums, they shut down the show.

Freedom of expression is at the top of the authoritarian hit list and the institutions that declare themselves devotees and caretakers (gatekeepers?) for the arts have a responsibility beyond just looking good and sounding smart. For all my shit talking I actually do believe all those glossy brochures and pleading at the podium about the value and importance of art: art is powerful, transformative, healing, essential, vital to a healthy society…which is exactly why the arts are a necessary part of the resistance to fascism and should be wielded as such.

It takes bravery to unleash institutional power and become a lighthouse in this worsening storm. I have a hard time believing that enough major institutions will lead with their artistic side instead of their institutional side. Gross evidence of this is the Academy’s response to the kidnapping and brutal beating of Palestinian director Hamdan Ballal, who they just honored with an Oscar! Not every institution will be presented with such an obvious opportunity to speak up on behalf of humanity. But when they are, will they be able to speak in a language other than delusional neutrality? It’s the soulless political branch of Institutionalized Art English.

Beyond statements and programming decisions, choosing to lead as artists is also about asking different questions. Like in the low stakes museum AI example, it’s asking “What can we make from this?” instead of “How can we control this?” It’s questioning admission price structures when people are losing their jobs en masse and the social services that helped with basic survival are being looted by the richest man in the world. It’s asking how to fulfill the promise of “Everyone is welcome” when the federal government and half the country wants to see so many of us disappeared, deported, or dead. It’s running the numbers to reallocate a percentage of the pretty party budget for donors to an emergency legal fund for the most vulnerable workers. That requires creativity, that requires humanity. There is another way this story can go.

Institutions will disappoint us, but I do believe in artists. This recent interview with Rhiannon Giddens was fantastic. The following quote stuck with me, and while I don’t want to take it out of context, I think it is a perfect summation of how to manage expectations of museums and cultural institutions:

So, my idea of what the mission is and somebody else’s idea of what the mission is are not going to be the same thing. There’s a reason why I’m not a multi-millionaire. If you are a multi-millionaire, there are reasons why. No shade, whatever. It means you do things in a certain way.

Rhiannon is a light. Brandee Younger and the music of Alice Coltrane are lights. So are the novelty museums and their wacky fire hazards, and the artists who are driven by the fight instead of the spotlight. Enough lights stacked on top of each other and look, now we have a beacon. Or whatever this thing is:

To cheer us all up, here I am taking RhiRhi out of context again. There are terrible men making greedy decisions that hurt us all but you can still fuck with their money.

Bryan Stevenson’s Equity Justice Initiative also opened up a third Legacy site last year, please read this piece by Doreen St. Felix to learn more.

"Hope," wrote Balzac, "is a memory that desires." This twinning of memory and desire helps clarify how the myths of modernity circulate with such powerful force. ... [Balzac] distinguishes between history (that which is ordered and laid out) and memory (that which lies latent and unstructured but which can erupt in unexpected ways). ...Memory is, in Balzac's judgment, "the only faculty that keeps us alive." It is active and energetic, voluntary and imaginative, rather than contemplative and passive. It permits a unity of time past and time future through action in the here and now, and therefore can erupt...at moments of danger. It brings into the present a whole host of powers latent in the past that might otherwise lie dormant within us. - David Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity, 2003